Art and China's Revolution.

Defying heavy snow that kept most other Ciszekians indoors, on Saturday afternoon I trekked down to the Asia Society on the Upper East Side to see an exhibition entitled "Art and China's Revolution." Having read favorable reviews of the exhibition in the New York Times and elsewhere, I had been meaning to check out "Art and China's Revolution" since it opened in early September but never quite got around to it over the course of a very busy fall semester. I finally got to the exhibition a day before it closed, and I'm glad I had the chance.

"Art and China's Revolution" considers the development of the visual arts in China during the first three decades of Communist rule. Seeking to inculcate 'revolutionary' values in the Chinese people and to purge Chinese culture of elements deemed incompatible with life in a putatively 'new' society, the government of Mao Zedong promoted the work of a new generation of painters schooled in the Soviet style of socialist realism while condemning traditional Chinese painting styles as decadent and outmoded. Despite their disdain for Western imperialism, Mao's cultural commissars seem not to have grasped the irony inherent in their rejection of China's artistic heritage in favor of aesthetic values borrowed from the Soviet Union. As "Art and China's Revolution" makes clear, socialist realism did not appear in China as an indigenous movement but was introduced as part of an official cultural policy which included student and faculty exchanges between Chinese and Soviet art academies as well as an explicit copying of Soviet works. Meanwhile, artists working in traditional Chinese styles suffered serious persecution - including physical and psychological abuse at the hands of frenzied Red Guards amid the chaos of the Cultural Revolution as well as years of imprisonment and the destruction of many of their works.

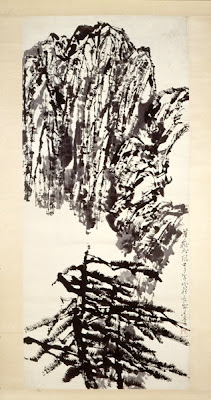

"Art and China's Revolution" covers a broad array of works, including examples of the traditional paintings that Mao disdained, propaganda posters celebrating his regime, and works produced in secret by artists who chose to work outside the limited bounds of expression permitted by the authorities. The three images shown above should give a sense of the great range of works represented. The first image offers an example of traditional Chinese ink painting in Pines at Hua Shan (1972), a hanging scroll by Shi Lu, a respected painter who endured torture and banishment during the Cultural Revolution. Produced in the same year as Pines at Hua Shan, Wu Yunhua's painting Mao Inspects Wushun Opencut Coal Mine (second image) contrasts dramatically with Shi Lu's work in both style and theme. In accordance with the canons of socialist realism, subtlety, subjectivity and symbolism have been rejected in favor of an ostensibly realistic but oddly cartoonish tableau of smiling workers surrounding their Great Helmsman. Ma Kelu's Morning Snow (1975) is an example of the work of an underground artistic collective called the 'No Name Group.' Painting in Western styles while rejecting the narrow strictures of socialist realism, the members of the No Name Group reaffirmed art's power as a vehicle of individual self-expression.

Taken together, traditional Chinese scrolls and the modern works of the No Name Group offer a strong but subtle indictment of the socialist realist style so ardently promoted by Mao. For all the smiling faces and displays of collective enthusiasm found in the official works included in "Art and China's Revolution," the exhibition reveals the hollowness - soullessness, really - of socialist realism. The apparent joy on display in these works is really something like what Dmitri Shostakovich supposedly spoke of (with reference to the final movement of his Fifth Symphony) as "rejoicing [that] is forced, created under threat . . . It's as if someone were beating you with a stick and saying, 'Your business is rejoicing, your business is rejoicing' . . ." By contrast, works like Pines at Hua Shan and Morning Snow reflect the spirit of authentic humanity reflected in an artist's personal vision. This spirit reminds us that the beauty that we find in art is the only justification that art requires - it need not be politically or socially useful, nor must it reflect the views of anyone other than the artist. "Art and China's Revolution" offers a potent reminder of this truth. AMDG.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home